Rope, rickety anchors, lobsters, bowel buckets, getting on the sauce and, oh yea, Bahama bonefish.

By Dave Ames

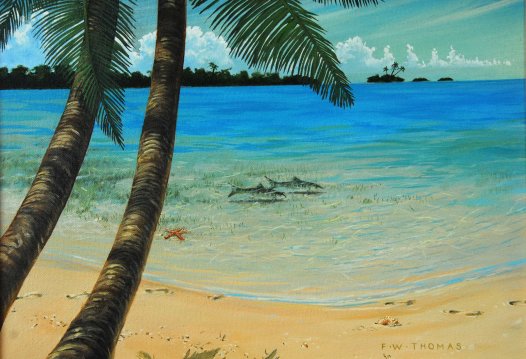

Note: Dave Ames is an awesome writer and great guy to party with because he likes to tip a cup, as you’ll learn in this story, and he’s a musician. Give him an inch and he’ll be plucking a guitar and howling at the moon. Ames was kind enough to share this read with Angler’s Tonic. Make sure you check out his book-length works, True Love & The Woolly Bugger and Dances With Sharks. Seattle-based artist Fred Thomas provided the artwork for this piece. The color bonefish painting is available for $1,000. Contact the artist and check his other works at www.fwthomas.com

TINY IS CALLED TINY because he’s so big; by himself he took up half the galley.

“Welcome to thirty-nine feet,” he said.

Thirty-nine feet on Tiny’s sailboat buys you an aft cabin, a forward cabin, a galley in between, and a cockpit up above. The plan was that, weather permitting, Tiny, Montana, and I would sail south from Abaco through the Bahamas in search of virgin bonefish flats. The problem was that the weather simply didn’t permit.

In a week we’d sailed only as far as the other side of the island. At least the part about the bonefish had come true. We were anchored in a salt creek alongside a flat so vast it stretched out of sight at low tide. If waking up surrounded by tailing bonefish is your dream, then we were living it.

It’s just another example of why you should be careful what you wish for. Tiny stood in the cockpit angling the transistor radio up toward the leaden morning sky, trying to improve the reception so we could pick up the weather report.

”When you’re at sea and searching for land,” he said as he pointed the antennae in different directions, “The same technique applies. Just follow the radio signal in the direction in which it is strongest, it’s one of the earliest forms of radio-navigation.”

From transistor radios to GPS satellite signals we’ve come a long way in the last few decades, but sometimes the old ways are still best. Especially if you don’t have the new ways, and the Christian Reggae gospel music on the radio finally gave way to the forecast. The station was run by a former cocaine smuggler who had found the Lord in an eight-by-ten cell, and the Born-Again Smuggler summed things up the lilting baritone.

“Dere could be a time when de weather been so far chilly for so far a time,” he said, “But I don’t know when that extended period might be.”

The Born-Again Smuggler went on to predict torrential rain, hail, lightning, and fifty knot winds out of the northwest. Tornados had been spotted in Florida, and the front was coming our way. It was just the latest storm to batter us since we’d moved aboard the sailboat, and Montana laughed maniacally.

“Tornados,” he said, “And I thought I had trouble casting before.”

Montana laughed so hard he choked. His breakfasts consist mostly of nicotine and eggs, hold the eggs, so when he finished coughing it was time for a cigarette. Montana slid forward between the taut wire halyards to the bow and flipped his silver Zippo lighter. His grey beard grows straight through to his eyebrows, and I watched, as always, wondering if this would be the time he set himself on fire.

“Hey,” he said, “There’s a lobster.”

Tiny’s blue eyes lasered out over his steaming coffee.

“Crawfish,” he said. “You sure?”

The cigarette safely lit, Montana used it to point at the bottom.

“There’s another one,” he said.

As luck would have it, we’d anchored over the mother of all lobster holes. Tiny moved like a cat, if the cat was fifty-eight years old and as big around as a beer barrel, so excited at the prospect of shooting something he was almost slobbering as he squeezed into a shorty wet-suit that fit him like a black rubber thong.

Tiny flopped overboard with mask, fins, and snorkel into water so shallow he couldn’t even do a proper dive. His green flippers waved madly in dry air as he kicked, and when he spun back upright a lobster writhed at the end of his spear.

“Yank his sorry crawfish ass off,” he said. “There’s another one down there so big I can’t span his back with my hand.”

I took the spear and slid the hard lobster carapace off the hinged barb into the sunken cockpit. The lobster flopped on the floor, a hole through his head. I gave the spear back to Tiny, who dove and came up cursing as he spit his snorkel.

“I missed,” shouted Tiny. “He’ll head for a hole, watch where he goes.”

A lobster the size of a small brown dog slipped under the keel and kept right on going, following its frantically flipping tail toward Cuba. Meanwhile, back on the port beam, Tiny surfaced with another yellow-red lobster writhing on his silver spear.

“Got another shooter?” I asked.

“Oh, yah, mon,” said Tiny. “You want to try?”

Boy did I.

They say there’s no cure for a hangover but try swimming in a cold ocean without a wetsuit shooting lobsters through the head. It takes patience. You have to wait for a good shot. The lobsters hang back in their holes, especially if their buddies are disappearing at their sides. At first all you’ll see are the serrated antennae, jutting out, but lobsters are like teenagers. Attention span isn’t one of their strengths.

Before long, they’ll be showing their heads. And when they do, it’s death from above. Put your eye to the spear and sight down the length of it to the knobby ridge behind the bulbous lobster eyes as you pull back on the rubber shooter, then let her rip.

The shooter only has two parts, a piece of wood with a hole in it and a loop of surgical tubing. You back the spear through the hole in the wood and notch the spear shaft into the drawn tubing, holding the wood with one hand you pull back on the rubber with your other hand.

Pull back hard, you want the spear to pierce the lobster. Ideally you’ll pin him to the sand. That lobster will be flopping, flipping, twisting and turning. The last thing you want is for him to escape. Not only will he die, you’ll go hungry. Something is going to eat him, but it won’t be you, and that’s why you peer down the shaft into the lobster’s head until long after you’ve released the spear.

It’s the trick to shooting anything, from a basketball to a gun. Look your shot into the target. Concentrating on the target reduces the tendency to flinch at the moment you release the shot. I was so focused on a lobster that came from a hole and was slowly crawling through the turtle grass that it was almost a surprise when my spear appeared in his head, I had him!

An hour later we had a dozen lobsters in the cockpit of the boat, alive for the execution as Tiny ran the thin tip of a fillet knife around the joint where tail meets body. The tails popped right off, then Tiny broke off a piece of a lobster’s antennae.

“What we gotta do now is get the shit vein,” he said.

The shit vein is the thin black bowel that runs through the tail, and Tiny inserted the jagged antennae up the lobster’s white puckered butt.

“Sorry, buddy,” said Tiny.

The serrated ridges on the antennae caught up like Velcro in the guts. When he removed the antennae the bowels came along for the ride, and just like that, the lobster tails were ready to cook. Cleaning the animals you kill is generally a lot more work than that, and Montana saluted with a beer.

“Cool,” he said. “Lobsters come with their own tool kit.”

With dinner secured, the next order of business was a tricky one. We needed to turn the boat around, to spin it 180 degrees, so that the bow and not the stern would be facing the northwest when the front hit later that evening. What made it tricky is that we were surrounded by bonefish flats, anchored in a channel not much wider than the boat.

What made it trickier still was the fact that we had three anchors out. We needed the engine to turn the boat, and with Tiny at the helm, steering, that left only two deck hands to simultaneously tend three anchor ropes as the boat spun. The plan was that Montana would loosen one rope in the bow then run to the stern to haul another, even though the last time Montana ran is never. We practiced two dry runs then Tiny said:

“You boys ready to haul some anchors?”

The problem with moving anchors is they’re heavy. If you’re an old guy, past your intestinal prime, hauling anchors can make you squeeze when you didn’t mean to squeeze and Montana pulled at his beard.

“Maybe I better use the head first,” he said.

I don’t know why they call it a head since it’s where you put your ass. Maybe because it’s where you do some of your best thinking. A head on a boat is the toilet, and there are no secrets on a thirty-nine foot boat. All your strengths, all your weaknesses, all your idiosyncrasies, they’re available for scrutiny.

Especially mine. All you can do is hope people pretend not to notice. It’s like a family curse. My stools come out more like easy chairs and overwhelm even the most touted of toilets; the wheezy little hand pump with leaky seals in the head didn’t stand a chance. After the first day I was using a bucket in the open stern.

We all get tired of our lives now and then, and there’s nothing like shitting in a bucket to make you appreciate your pedestrian life at home. Privation is good for the soul. The first thing you learn is how much of your life is superfluous. You see how much fluff there is to civilized life, how much you can live without.

At least that’s what I told myself as Tiny started the motor and put the sailboat in gear. Sweat dripped off the end of my nose onto the incipient hernia in my once flat belly as I hauled anchor rope. Up in the bow, Montana freed one rope and started for the stern to haul another. Everything went according to the plan for maybe ten seconds when the engine revved up way too high then died completely.

“Yah-ah-ah!” screamed Tiny, the panic evident in his voice.

Then he jumped over the side of the boat.

We were sideways to the wind, which had blown us so close to the flat that I couldn’t believe my eyes. Bonefish were tailing in the shadow of the boat. I was watching the fish as I cleated in the rope to the anchor I was tending to keep the boat from swinging any further, and nearly caught a finger in a half-hitch as the knot cinched down. I was thinking how the only way to free my hand from that knot would have been to cut off either the rope or my finger when Tiny came up spluttering.

“OK,” he said. “Nobody panic. We still got an anchor left.”

And not just any old anchor either. This anchor was the biggest one yet, the hurricane anchor, and Montana was bleeding from both hands before he’d wrestled it free of its home in the bottom of a cockpit compartment.

Our situation was precarious but not yet dire. When Montana had freed the bow anchor, the tide had washed the rope into the moving propeller, winding it tightly around the shaft. The one thing that had to happen and had to happen fast, before the tide turned, was that we needed to move the Hurricane anchor into a position so that we could pull tight to that anchor, thereby relieving the tension on the rope anchored to the propeller, which we could hopefully then unwind without cutting the rope, which we still needed to get ready for the coming storm.

Moving a boat by pulling on ropes connected to strategically placed anchors is called kedging, a practice as low-tech as it gets. Once we’d relieved the pressure on the rope fouled around the propeller the snarl was surprisingly easy to unwind, and for the next hour we kedged anchors with brute force and a rubber dinghy until we had it right.

The boat faced directly to the northwest, with three anchors set forward into what would be the teeth of the coming storm, and one anchor to the stern to keep the boat from swinging in the tide. There was more work to be done but I was Jonesing bad. While we’d been setting anchors, the bonefish had been tailing, and I saluted.

“Captain Bligh,” I said. “Permission to go bonefishing.”

Tiny muttered. “It’s a mutiny,” he said.

But he was just kidding. He knows how I feel about fishing, and if the downside to being anchored alongside a bonefish flat is that you might run aground, the upside is a short commute. With a box of flies in my pocket and a rod in my hand I was ready; a ten-second dinghy ride later I was knee-deep in a falling tide on a hard sand bottom.

The strongest tidal wash leaves only sand. Flows with a little less energy allow turtle grass to grow, and as the tidal currents decrease first red then black mangrove will appear. Big Sandy Flat is a high energy zone. There’s only the slightest chunk of red mangrove on the highest point, most of the rest is sparse turtle grass. The end toward the ocean is forty acres of pure white sand, and the bonefish travel in packs, a dozen to fifty fish at a time.

The wind was picking up as it clocked around in advance of the coming storm, and bonefish don’t seem to like the wind any more than people do. Maybe it’s because a bonefish’s sense of hearing is so acute, and they can’t hear in the wind. I’ve heard guides say it’s because bonefish don’t like the feel of wind on their tails. At any rate, a mangrove lee is always a good place to look for fish in the wind.

I stepped over a giant red starfish, keeping an eye on the three meandering blacktip sharks basking in the warmer water in the mangrove lee. A battleship grey stingray hovered past on round fluttering wings, then another. Sharks and rays mean a flat is alive. There will be some bonefish around, and I hadn’t been fishing five minutes before the tip of a pointed silver tail gave away a school of bonefish.

On any given flat, the first fish of the day is usually pretty easy. One cast is all it took, and the hooked fish ran and ran, spooking up three more schools. Disturbed fish are much harder to catch, and the first darting schools spooked up more schools that zigged and zagged across the flat leaving trails of nervous water like prop wash.

There is such a thing as too many bonefish. Catch one, spook fifty. Catch two, spook a hundred. Catch three, four, five; spook…I have no idea. It was more bonefish than I’d ever seen in one place before as the individual bands of bolting bonefish coalesced into one giant school over the white sand at the drop-off into deeper water.

The fish swirled and whirled, making up their collective mind, visibly startled at the low rumble of distant thunder. I looked up, a sharp-edged wall of bruised purple and black clouds stretched from the water to the sky as far as you could see in both directions. One-one thousand, two-one thousand, three….the distant flash of lightning didn’t come until the eight count.

The fish could have dropped off the flat in the falling tide, but they wanted to fill their bellies in anticipation of the cold weather they knew was coming. At least a thousand skittish bonefish flooded back up onto the flat for one last feeding run. The front was coming, but so were the fish. It was just a question of what would arrive first.

All I had to do was wait.

With spooky fish it’s best to cast the fly well in front, let the fly sink to the bottom, and move the fly only when the fish are above it. With a school of really spooky fish, don’t move the fly until the lead bonefish have already passed. Those outside bonefish are like watch dogs. They’ll spook at anything, even the movement of your fly, so you cast, and then you wait.

Then you wait some more.

The bonefish darkened the flat as they came toward me, hundreds and hundreds of fish. I was on both knees in the sand, so low I was sitting back in the water. I could have stripped my fly, but I didn’t. The wall of advancing fish was just too exciting. I was stretching the moment out, and the lead fish were only a couple of rod lengths away when the entire school broke at a detonation of thunder so loud it seemed like it came from between my quivering ears.

If the bonefish had been buffalo I’d have been trampled. It was a stampede. Bonefish ricocheted off first my legs then my ankles. I lifted the rod which moved the fly as I lunged to my feet, inadvertently hooking a fish which wasn’t even into the backing when a jagged bolt of blue lightning blasted the open ocean just north of the flat.

Standing in the ocean holding a graphite fly rod up to a lightning storm is a poor plan if you hope to celebrate your next birthday. I broke off the fish and ran for the sailboat, wondering how much safer it would be sitting beneath two aluminum masts. Fortunately, there’s more than one way to get fried. If the lightning didn’t get us, the martinis would. Down in the cockpit Montana was dispensing adult beverages, shaken not stirred, so cold that humidity condensed on the outside of the tin cups.

“Cheers,” he said.

I clinked my tin up on first his cup, then Tiny’s.

“Ch…” I said, then we all looked up.

In the space of half a word, that’s how quickly the storm washed over the boat. We’d left a bucket on deck as a rain gauge, in the first ten minutes two inches fell. The wind was howling so hard you had to shout to be heard, then it really began to blow.

Tiny beamed. “It’s gotta be blowing fifty knots,” he said.

He was pleased because the boat was barely rocking. All that kedging of anchors had worked. Inside the cockpit it was so calm you could blow smoke rings, and after a second cocktail I put a pot of water to boil on the three-burner propane stove.

“Lobster, anyone?” I said.

Tiny was so wound up he was chopping at the air with his hands.

“In the old days,” he said. “Any day you had dinner, that was a good day. Against all the odds, you’d persevered. You’d lived.”

Surprisingly, the part of the day that had given me the most pleasure wasn’t the lobsters or the bonefish. It was moving the anchors. It was prevailing over adversity. When you’re alone on the ocean, it isn’t like one of those ridiculous reality shows. No helicopter is going to come rescue you. Nobody’s going to vote you out of the tribe.

You have to do it on your own, and when you do, there’s no feeling like it. Your life depends on having the proper equipment, and as the storm raged about us Tiny and Montana lifted their tin cups, toasting the first two Laws of the Sea, the gospel according to Tiny, who should have known, since he’d sailed around the world.

“You can’t have too much rope,” he said.

“Or too many anchors,” said Montana.

Then they both looked at me, waiting for the third Law, which they thought of as my Law. Like I said, there are no secrets on a thirty-nine foot boat. I’d been told, but I’d forgotten, and if you’re living on the edge, away from the customary amenities of modern life, it’s a mistake you’ll make only once, and I lifted my cup to Tiny’s third Law of barebones sailing.

“Never shit in a dry bucket,” I said.

Put some water in it first, because if you make a mess, it’s your mess. Nobody else is going to clean it up for you and let’s face it: life is too short to be cleaning buckets, when you could be fishing.