How we won the cold war and lost the world’s greatest trout.

Editor’s Note: This amazing story tells about a few American angling junkies, including Alaska author Rene Limeres, who opened the Russian hinterland to angling for taimen. It’s a long read so our suggestion is to print it out, grab a glass of vodka and find your favorite chair. Well worth your time and not a bad excuse for a drink.

By Rene Lemiers

It was getting late, and through the vodka haze and smoke I could see trouble brewing in the dimly lit bar. My buddy had just beaten the big Russian in arm wrestling and the bruiser didn’t like it too much. In addition, his beautiful and drunk girlfriend was getting a little too chummy with me. So it was a good time to get the hell out of there.

I staggered to my feet, called over to my friend, and we left with Nina and Tanya and the others.In the taxi, on the way back to the hotel, my chaperone reminded me, quite sternly, of our special mission, which wasn’t to sample all the vodka and women of Russia. I smiled. Tanya from Khazakistan had jet-black hair, blue eyes and a perfect figure no amount of clothing could hide.

It was St. Petersburg in the late 1980’s, and decades of Cold War tensions were lifting like heavy fog off the Neva River. I was with a group of Americans finishing a whirlwind cultural tour of Russia as part of a great adventure that had its beginnings several years prior. We had toured in grand style the Kremlin and Red Square, dined in the best restaurants of Moscow, marveled at the art of Le Hermitage and palacial digs of Peter and Katherine, and taken in the magnificence of the cathedral of St. Isaacs. But the best was yet to come, for we were set to pursue one of Russia’s true legends, a fish fable that

had tantalized westerners for decades, and we were to be among the first to see if it was true. It was sometime during the early 1980s when I had first heard about it. There was an article in the back pages of a major West Coast paper, about some scientists trying to verify the existence of a mysterious fish, found in a lake in a remote province of northern China, that reportedly reached lengths up to 30-feet long, creatures only seen during great natural disturbances, like right before major earthquakes. No way, I thought. But not long after, there was a follow-up piece that claimed these fish were believed to be an isolated form of a trout-like species called taimen, found only in Asia, that were known to reach lengths of eight feet or more. Now that got my attention.

I did some research and came up with some fascinating tidbits on these so-called taimen. They are believed to be relicts of an ancient species that gave rise to our modern day salmon, trout and char. In addition, they are extremely long lived, with longer potential life spans than humans. And though they originally were found from the headwaters of the Danube across Asia into China and Korea, the largest recorded forms have all been from the big rivers of Siberia, where fish have been taken well in excess of 200 pounds.

If there was any place a 200-pound prehistoric trout could hide from relentless hordes of modern-day fly fishermen, it would be in the trackless expanses of Siberia, the “mother of all wilderness.” The legendary land of exile and mind numbing winters had been off limits for decades and now it was opening. God only knew what other mysteries it might hold.

Determined to learn more, I delved deeper into the taimen mystique, until I became ensnared by it, thinking of little else during my waking hours. These big old fish were smart, cunning even, and their legendary prowess was woven into the folklore of Siberia and central Asia in fantastic tales that set the imagination reeling: fish swallowing people whole; starved nomads hacking pieces off a frozen carcass all winter (which comes to life in the spring and swims away); trees ripped from banks by fish grabbing bait on set lines. The stories went on and on.

I became obsessed with the thought of checking out these mythical creatures on my own, but how in the world? The Iron Curtain was ready to fall, but was still a formidable barrier to most Americans of average means, like me. Somehow, someway, I just had to catch a taimen.

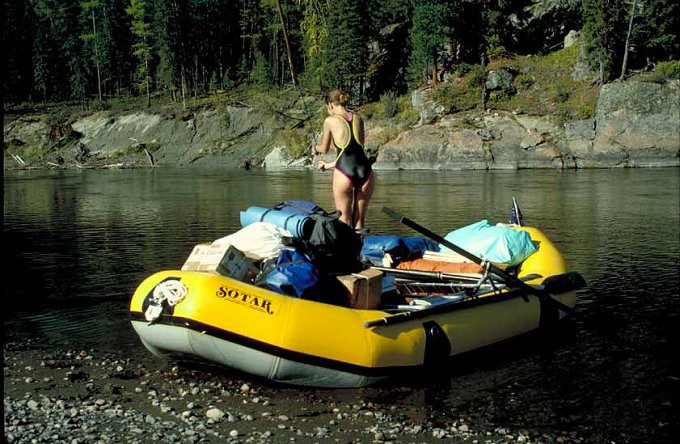

There was a guy I knew who sold SOTAR rafts and his own hand-welded frames out of a garage in south Anchorage. Eugene Vogt III, or Goo as everyone knew him, was a Louisiana boy who had migrated north, first to Montana, then to Alaska, to pursue his passion for whitewater rafting and hunting. The existence of giant, primordial fish predators lurking in the remote rivers of Siberia was a novelty not lost on someone from the land of big gators and gars. Goo (with some prompting) became keen on chasing these things, as it fit right in with his personal quest to do whitewater trips in the wildest reaches of the world.

His reputation as a boatman had led him into the international whitewater rafting scene, where he competed in annual rallies on some of the most prestigious rivers on the planet, in places like Turkey, Australia, central Asia, the American West, etc. It was a great gig for someone like him. See the world, make new friends, do a little rafting, do a whole lot of partying, and meet lots of girls.

The Russian team was always well represented at these meets and they had the prettiest and most articulate translators. These girls, like Natasha Karpiva, Nina Kusorokova, and others—all beautiful, vivacious and friendly—made it real easy for Goo to become acquainted with the Soviets and cultivate relationships that were to serve him well in the years ahead.

Now Goo’s Russian rafting buddies were well connected, in ways he could have never imagined. They were sponsored by the Soviet Peace Committee, a Russian non-profit established after WWII that over the years had been infiltrated by the KGB. Some of the team members were actual spooks, intent on investigating the inscrutable ways of Americans, and the girls were handpicked from the brightest, prettiest and most fluent young women in Russia—they were just bait, to draw guys like Goo in and get them to open up and talk about their innermost secrets and desires.

One of the things the Russians couldn’t get a handle on was the concept of catch-and-release sport fishing. When Goo told them there were Americans who would pay big bucks to chase fish halfway around the world, just for the fun of it, they couldn’t believe it. What were these crazy American-skis really up to? They were determined to find out.

At a rally on the Chuya River in the Altai Mountains of central Asia in the late 80’s, the Russians met with Goo and discussed plans to make his longtime dream of a Siberia river expedition come true. All he had to do was get some fishing clients and another guide and they would take care of all the details. The trip of a lifetime was on.

Though Goo and I talked many times about the possibility of doing a trip over there, I never let myself believe it could happen until I got his phone call, early in the summer, right after my oldest daughter was born. Goo was ecstatic, but my excitement was tempered by the sobering responsibilities of new fatherhood. I told him there was no way I could even consider taking off for Siberia at that time. But I signed up for a crash course in Russian and bought my plane ticket that same day.

Though we would eventually make dozens of trips to Russia, that first time was a magical stroll down the yellow brick road, into the forbidden land of mystery that was Russia to anyone who grew up during the Cold War. To someone like me, who had never been too far out of the U.S., it was a mind-altering experience.

One of the things we agonized over, in the weeks before our trip, was having adequate gear. So we scoured the world of angling for tackle that we felt would be up to the task. This included the stoutest rods and sturdiest reels made for freshwater, along with the largest flies, spoons and plugs. Much of what was available, we concluded, was not up to snuff, so we improvised. I tried my hand at taimen flies, and came up with some of the scariest looking creations I’ve ever tied, using whole squirrel and weasel skins and tandem 7/0-9/0 hooks. From big dowels, Goo carved enormous, jointed, topwater plugs, which he painted black and festooned with bright red plastic eyes, long leather tails and giant whiskers. They looked like something out of a nightmare. (When he showed them to the Russians, they refused to let him use them, claiming they would scare off the taimen!)

We hadn’t a clue what we were in for when we boarded an SAS jet one mid-September to fly over the pole to Moscow via Copenhagen, and had we known what we know now, we would have been prepared for much more than just fishing. You see, the closest thing Russia had to legitimate trip outfitters in those days were state-sponsored organizations that were set up during the Cold War to coddle top Soviet military brass and politicos with a little soft adventure and lots of fine food, booze, and loose women. To them a fishing trip was nothing more than a big party on a river.

After our wild, four-day cultural introduction to Russia, we flew all night across Siberia to a country called Tuva, which lies in the heart of central Asia, right above Mongolia. I was in the fog of a monumental hangover, compounded by major jetlag, but I was struck by how much the country reminded me of parts of Montana, with open, rolling, grassland and highlands forested with giant larch, cedar and aspen. The rivers and streams were all clear-flowing runoff drainages that originate in the great arc of mountains that border the high plains of Mongolia, and form the headwaters of Russia’s greatest rivers, the Yenesei and the Lena, which flow north across the vast expanse of Siberia, hundreds of miles to the Arctic Ocean. It was on one of those remote mountain headwaters of the Yenesei that our great taimen hunt took place.

Now Russians have a whole different style of doing river trips, unlike anything we do in Alaska or elsewhere. Instead of floatplanes, they use military transport helicopters like the MI-8, which makes a formidable cargo plane capable of hauling an unbelievable payload. When we loaded up to go out to the river, Goo and I were astounded by the sheer amount of gear and food they threw into the back of that chopper: five rafts with frames and oars, sacks of potatoes and onions, heavy wooden crates filled with canned goods and big jars of pickles and beets, plus circus-sized tents and tarps, a complete kitchen, and enough beer and vodka for a small army.

The Russian guides, we quickly discovered, were the real deal—kick-ass, total animals (I thank God we never went to war with them). They could brush a campsite, cut, split and rack a cord of wood, erect a small tent village, and get a roaring fire and two giant pots of water boiling, all in the time it would take the average American ghillie to get out of waders and into camp clothes. No lie. It was quite an education watching them at work. But, the girls they brought on the river were the biggest surprise. Not just fit and good looking, they were also tough as nails. They could row boats, chop wood, cook awesome food, play music, and drink vodka and tell raunchy jokes damn near as good as any of the men.

You fall into an easy rhythm being on a river with Russians. You wake at dawn to the sound of them chopping wood for the fire, eat a light breakfast of their delicious crepes and stout coffee, and then break camp for an early start on a full day of floating and fishing. You make camp early each night and enjoy a fantastic dinner of Russian comfort food, made from scratch, followed by an evening of relaxation around the fire, playing music, singing, telling jokes, and drinking lots of vodka. But despite all the apparent joviality of our hosts, I was convinced as the days wore on that some of them were watching our behavior, waiting for us to slip up and drop the façade of the happy drunk fishermen and reveal our true identities as American spies. God knows it was difficult at times keeping up the charade. The days would warm under relentless clear skies, the fishing would go to shit, and the girls would take to modeling swimsuits. (A couple of the wenches even resorted to skinny-dipping!) Even I had a hard time concentrating.

Our interpreter, I remember, was all of 21, a vivacious and unbelievably attractive thing by the name of Lena Ivanova who was fluent in four languages. Just about every American on the trip hit up on her, but she obviously was on orders not to get too friendly with the clients. That is, until she drank too much vodka one night and woke up in Goo’s tent the next morning, which practically caused an international incident. She had violated an unwritten code of the KGB and slept with the enemy. The trip leaders, two cheerless blokes by the named of Tola and Valerie, were not too happy about it. Things got dicey and I wondered if some of us weren’t going to end the trip in a Gulag somewhere.

Things might have devolved to that had it not been for the Siberian taimen. Despite everything else going on, they remained the true prize that kept us all focused, proving much more elusive and fascinating then we ever could have dreamed. Solitary predators from an age long ago, they are scarce, territorial, and uncannily wise. (A trout that can live longer than you can get pretty wily in its old age.) Our native guides all had been raised along the upper Yenisei, and each knew every hole and big taimen by name. Through the years, as had their fathers, these guides had matched wits with the most wary of these primitive salmonids.

Our first taimen, I remember, was definitely no monster—maybe ten pounds, or so, but you’d have thought we’d caught a world record by all the fuss we made over it. It was awesome looking—sleek, with a body plan more like a lean bull trout than a classic trout or salmon, and a large head with piercing eyes and gaping mouth filled with teeth. The coloration was beautiful—greenish bronze layered over silver topsides and a whitish belly, with distinct, rosy-pink shading on its tail. Markings were sparse, like on a salmon. The whole demeanor was of a primal, voracious killing machine, like that of a northern pike, only more so.

The Russian tradition is to fish for the big ones late at night, when they leave their deep lairs and prowl the shallows for food—usually shoals of minnows, ducks, rats, lemmings, squirrels or, according to folklore, even hapless larger mammals, such as deer or wild boar. The natives toss giant, crude plugs, carved from wood or made from animal skins that imitate a drowning rat or squirrel, and work them through likely ambush sites in the pitch dark. (Flashlights are forbidden on late-night taimen hunts.) We found it difficult, if not impossible casting the humungous flies, even with big rods (11-12 wt.), and quite unnerving to have those big, deadly hooks whizzing around our heads in the dark.

Casting giant plugs in these conditions wasn’t much easier, as it was very hard to gauge your distance in the dark and not hang up on overlying branches or snags, and once you were, it was like hanging a grappling hook, almost impossible to free. Compounding that difficulty was the manner in which big taimen often hit prey on the surface at night. They frequently slap it with their tail to stun it (or check it out) before coming in for the kill. The native guides tried to explain the subtleties of the taimen take and other pointers, but our lack of comprehension resulted in much frustration and endless swearing on both sides.

Though some have said otherwise, a big taimen is quite a challenge on a fly rod, given its strength, the conditions they’re usually encountered in (in or off large, deep and swift lower main stems) and the fact that they’re such unpredictable fighters. Unlike a big salmon that panics and bolts for the main channel once it feels the hook, a big taimen might give you a few headshakes and hunker down in deep water for a monumental tug-of-war, or take off in a blitz into heavy water and spool you in seconds. Or it might even jump like a tarpon and scare the bejeezus out of you before it throws the hook back in your face. If they don’t win their freedom initially, at some point in the battle they’ll usually wrap themselves in your wire leader and part your line with two rows of razor-sharp teeth.

When all is done, if you’re lucky and skillful enough to tire out one of these leviathans, you still have to land the beast, which, for a large and canny old taimen can be a real trick. The Russians, of course, just shoot them, but that makes no sense for a fish that takes a half a lifetime to reach trophy size, and besides, it doesn’t make for a good “grip ‘n grin” to have half the fish’s head blasted away. Nope, you just have to herd them into the shallows and then, like a gator, wrestle ‘em into submission. Some of those big old fish will just sit there and sulk, like they’re all spent, but the instant you close in on them, they come unglued and beat the crap out of you and get away. It can be heartbreaking, especially with a potential record fish.

That first time around, we all had our shot with the BIG ONE. Early on, late one starry night after the rest of us had gone to bed, Goo was sharing the fire and some spirits with one of the guides, when, on a whim, he grabbed his rod and heaved a giant spoon into the swirling black waters not 15 feet from shore. The lure was instantly seized by a taimen that he swears to this day was bigger than he is. The fish instantly took off upstream, bucking the swift river current to spool him before he and the guide could get underway to pursue it in one of the boats. He was fishing an Ambassadeur 7000 loaded with 30 lb. Maxima, on a 30-40 lb. muskie stick.

I had my chance for glory on a similar night, fishing out of a longboat with one of the clients and a guide. I was working my giant squirrel imitation in the flat water of an immense slough, when I heard a loud slapping noise and felt my line tighten. I reeled down for a savage hook set, and as I struck the fish must have lunged toward me, throwing me off balance and nearly sending us all into the seething, cold river. I grabbed hold of the boat to keep from going in and the fish jumped twice—what a crashing sound it made in the dark! When I reeled in to recover the slack, the line had parted. That fish jumped three more times, each time receding farther into the blackness. It was definitely pissed.

We did some more trips with the folks from the Soviet Peace Committee; some of them memorable, and some we’d like to forget, but we never did find the Holy Grail for Siberian taimen. But in the early ‘90s, Goo connected with some real sharp operators out of the Far East hub of Khabarovsk on the lower Amur delta, who put him into some really great rivers where the taimen grow immense feasting on chum salmon. Goo and his fishermen took numerous line and tippet class records there, including, for a while, the All Tackle record. But, ultimately, the prize for the largest Siberian taimen ever taken with sporting methods (no shooting allowed) was a fish that weighed just under 100 pounds and was caught by Goo’s head guide, a Russian by the name of Yuri Orlov.

Russia has changed a lot over the years, most of it for the better. I find myself sometimes missing the good old days, with all its Cold War intrigue and the excitement of our first interactions. In the end, I think our Russian friends finally got it that most Americans go over there just to have a good time—to chase a few fish and some women maybe, and drink way too much vodka and beer, just like their Russian brothers. Last I heard, most of those KGB boys had gone on to better things, like making millions of dollars in joint business ventures. And the girls? The ones who spoke such good English and could make you fall so hopelessly in love, with their innocence and charm, sexy accents and exotic beauty? Just about all of them defected and married rich Americans and are no doubt enjoying the good life.

Things are pretty tame for me now. You reach a point in life when you realize that almost all your great adventuring is behind you. But, thank God, you think, you did enough in your younger, wilder days to suffice. I don’t need to be going on grand snipe hunts in foreign lands and on strange rivers anymore. But I did hear, not too long ago, about some catfish that gets as big as a grizzly and lives in the rivers of Thailand. The natives that fish for those leviathans lure them in with sacrificed animals, such as pigs and goats and sheep. Supposedly, those fish get up to ten-feet long. Hmmm, I wonder if the Thais have an international whitewater rafting team? I’ll have to ask Goo about that.

Rene Limeres is a longtime wilderness fishing guide and photographer based just north of Anchorage, Alaska. Intimately familiar with the angling scene in the 49th state, he has published and contributed to some of the best selling guidebooks on fishing Alaska. Rene also has been fortunate to fish many of the rivers in Russia’s Far East since the late 1980’s. To learn more about his fishing programs and publications, check out his website at www.ultimaterivers.com